Inspired by War, Commanders in Courage: For Women’s History Month, RPJ Honors Three Political Pioneers Inspired to Politics during Times of War

By Helen D. (Heidi) Reavis

It has always struck me as ironic that “Women’s History Month” comes just days after Presidents Day – which our law firm celebrates as “Leaders Day” honoring those who have fiercely led this country forward and, in some cases, made even more of an impact than Presidents but without the same recognition or reward.

HIStory forgets HERstory. There are no federal holidays honoring a woman. Any woman, in our 245 year history. A handful of states honor Susan B. Anthony’s Birthday (February 15, 1820), as does our law firm. However, Women’s History Month – as with Black History Month and other commemorative periods – while not a holiday, is in some ways a more important call for us to reflect, communicate and perpetuate the stories that each of us knows which didn’t make it to the front page. It’s the quiet back-stories more than the headlines that speak of the struggle, hard work and circumstances that propel one individual to action that could change the world.

In light of our firm’s custom of celebrating Leaders and changemakers who have broken barriers, we profile three American political “firsts,” women who, across the vast divide of time, place and race, were each trail-blazers sharing a common experience: each was living through turbulent wartime America, inspiring them to become civically involved: Shirley Chisholm (Vietnam War), Patsy Mink (WWII) and Jeanette Rankin (WWI). Each was committed to non-violence and inspired to enter politics to help steer the country toward a more peaceful and less hostile future. Circling back to Presidents Day, it bears noting these three women also share something in common with George Washington, called our “First of Every Thing,” who was personally motivated to enter politics by New England’s economic and political exploitation by the British. One can only hope the current War in Ukraine gives rise to new leaders as committed as those profiled in this article.

With the slogan “unbought and unbossed,” Shirley Chisholm from Brooklyn, New York, became the first Black woman to be elected to Congress and the first Black candidate to run for her major party’s nomination for President of the United States (in 1972), during the Vietnam War era. Chisholm never veered from her conviction that helping women, children and the disadvantaged would benefit America far more than funding the military and defense.

With the slogan “unbought and unbossed,” Shirley Chisholm from Brooklyn, New York, became the first Black woman to be elected to Congress and the first Black candidate to run for her major party’s nomination for President of the United States (in 1972), during the Vietnam War era. Chisholm never veered from her conviction that helping women, children and the disadvantaged would benefit America far more than funding the military and defense.

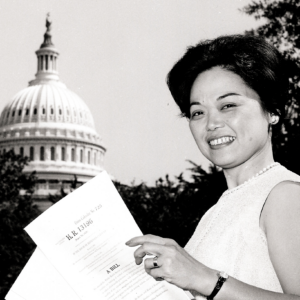

Patsy Mink from Hawaii while still a US territory and the target of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, became the first woman of color and the first Asian-American woman elected to Congress (in 1965) after Hawaii achieved statehood, and spent a lifetime on state and federal legislation advancing women’s and children’s rights and education, and was one of the architects of Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Patsy Mink from Hawaii while still a US territory and the target of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, became the first woman of color and the first Asian-American woman elected to Congress (in 1965) after Hawaii achieved statehood, and spent a lifetime on state and federal legislation advancing women’s and children’s rights and education, and was one of the architects of Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Jeannette Rankin, a pacifist from rural Montana, was the very first woman to be elected to the United States Congress (in 1916)—and the first woman to cast a federal vote. A working rancher from our early Western territory of Montana, Rankin was a life-long pacifist, championed the women’s suffrage movement, and ultimately drafted and brokered the 19th Amendment to our US Constitution.

Jeannette Rankin, a pacifist from rural Montana, was the very first woman to be elected to the United States Congress (in 1916)—and the first woman to cast a federal vote. A working rancher from our early Western territory of Montana, Rankin was a life-long pacifist, championed the women’s suffrage movement, and ultimately drafted and brokered the 19th Amendment to our US Constitution.

Courageous and ahead of their time, these three remarkable women and their families lived through war and converted tragedy and adversity into inspiration. They embody the power of healing and were pioneers in the expansion of civil rights in this country, in different ways but with shared goals, seeking to achieve a more inclusive and peaceful nation in which future generations could thrive – some of the same factors and conditions that inspired our early days and continue to inspire the pursuit of peace and inclusion today.

Know these names. Rankin. Mink. Chisholm. Know their stories. Unbought and unbossed – and undeterred.

Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Chisholm

Chisholm was the first Black woman in history to serve in the US Congress. She started her professional career running a day-care center for children in Brooklyn, and from that experience sprang her lifelong fight for early childhood education and child welfare.[1]

Born in 1924 in Brooklyn, New York, to Charles St. Hill, a factory laborer from Guyana, and Ruby Seale St. Hill, a seamstress from Barbados, Shirley Anita St. Hill was the eldest of four daughters.[2] She had high grades while attending public schools in Brooklyn, which gained her admission to some of the most elite colleges in the country but chose to attend Brooklyn College on scholarship, where she graduated cum laude with a BA in Sociology.[3] After graduation, Chisholm worked as a nursery school teacher and then as the Director of two daycare centers.[4] In 1951, she earned a Master’s Degree in Early Childhood Education from Columbia University. Chisholm then served as an educational consultant for New York City’s Division of Day Care, which sparked her interest in politics as a means for creating change.

Chisholm was conscious of the racial and gender inequalities that were all too common at the time, including the Vietnam War draft which heavily impacted Black communities. She was also ahead of her time in seeking a divorce from her husband, but kept his name in politics. Chisholm became an active member of several organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the League of Women Voters, and the Democratic Party Club in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.[5] She was building a platform and ready to mount the political stage.

In 1964, Chisholm successfully campaigned to become the second African American to serve in the New York State Legislature. Four years later, she ran for Congress – after a court-ordered re-districting created a new, predominantly Democratic, district in her neighborhood.[6] But her campaign was not an easy one to lead. Chisholm faced competition from three other African American challengers who were more renown and better financed. Determined to distinguish herself, Chisholm obtained a sound truck and drove around the new Congressional district announcing, “Ladies and Gentlemen… This is Fighting Shirley Chisholm coming through!”[7] Her unique campaign, tenacity and personal style, gave her the edge she needed. As she noted, “I have a way of talking that does something to people … You have to let them feel you.” And they did.

Chisholm also used gender to her advantage. She faced well-known Republican-Liberal James Framer in the federal election, who was at the forefront of the civil rights movement and an organizer of the Freedom Riders.[8] However in his campaigning, Framer took the position that “women have been in the driver’s seat” in Black communities for too long and it was time that a man took over, not a “little schoolteacher.”[9] Chisholm used Farmer’s rhetoric to shed light on the discrimination that women face, with her campaign motto, “Unbought and Unbossed.” In addition to her advocacy for women’s rights and the rights of children and families, Chisholm leveraged her fluent Spanish to appeal to the large Hispanic population in her neighborhood. Chisholm won the general election with 67 percent of the vote.

The Vietnam War was at its height and the impact on communities of color profound. Chisholm delivered her first speech on the floor of the US House of Representatives in 1969, standing up to President Nixon and her fellow legislators. She advocated against the Vietnam War and vowed to vote “No” against any defense appropriation bill, “until the time comes when our values and priorities have been turned right-side up again.”[10] “Congress can respond to the mandate that the American people have clearly expressed,” Chisholm told her fellow legislators. “They have said, ‘End this war. Stop the waste. Stop the killing. Do something for our own people first.'”[11]

Those remained her key themes when, in 1972, Chisholm made history, again, to became the first African- American to run for the Democratic Party’s nomination of a candidate for President in 1972. Chisholm never veered from the conviction that helping women, children, and the disadvantaged would benefit America far more than the funding of the military and defense. Just over a year later, her hopes were realized when the last remaining US troops pulled out of Vietnam.

Patsy Mink

Patsy Mink, whose ambitions were sparked while Hawaii was still a territory of the United States, became the first woman of color and the first Asian American woman to serve in the US Congress.[12] Originally interested in medicine, she turned to law and politics after being rejected from medical schools, and observing the discrimination faced by her family during and after World War II.

Mink ran for office after Hawaii achieved statehood in 1954. Throughout her many terms in office, Mink was a passionate advocate for civil rights, education, and women’s rights. She authored and co-authored several fundamental bills and was one of the architects of Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Early Childhood Education Act, and the Women’s Educational Equity Act. She went on to become the first person of color and first Asian-American to run for President.[13]

Born Patsy Matsu Takemoto on December 6, 1927, in Paia, Hawaii, Mink’s parents were both from families who emigrated to the American territory of Hawaii to work in sugar plantations. Her father, Suematsu Takemoto, was a civil engineer of Japanese descent, and her mother worked at home.[14] Growing up, Mink observed the discrimination her father faced as he was repeatedly passed over for promotions in favor of White Americans. Mink also experienced discrimination herself and xenophobia at school, which made her feel isolated. Seeking better opportunities and greater tolerance, the family moved to Honolulu shortly before the bombing of Pearl Harbor.[15]

Mink’s political achievements started early. At Maui High School, Mink was elected Class President and Valedictorian. She then attended Wilson College in Pennsylvania and then the University of Nebraska, where she experienced racial discrimination as students of color were not allowed to live in the same dorms as White students.[16] In her junior year of college, Mink was diagnosed with a thyroid condition that required surgery and she decided to move back to Honolulu, where she completed her undergraduate studies at the University of Hawaii, with the goal of becoming a doctor. During Mink’s time there, she joined the Varsity Debate Team and was elected President of the Pre-Medicine Students Club. Despite her impressive academic record, none of her medical school applications were accepted.[17]

However, Mink’s interest in politics continued to grow, particularly in the anti-war movement after World War II. She eventually decided to pursue a law degree and was accepted at the University of Chicago Law School. After graduating in 1951, Mink returned to Hawaii with her husband, fellow law student John Mink, and their daughter.[18] Hawaii had not yet achieved statehood at the time, so running for office was still a pipe dream.

After passing the bar exam, Mink was unable to secure a job due in her view to gender discrimination and prejudice against her interracial marriage. As a result, she founded her own law practice. With this, Mink became the first Japanese-American woman to practice law in Hawaii, still a territory at the time.[19] Additionally, she worked as a private attorney for the U.S. House of Representatives in the Hawaii territory and established the Oahu Young Democrats in 1954.[20]

Following Hawaii’s statehood in 1959, Mink wasted no time and began campaigning to become the state’s first Congresswoman. Her initial attempt at the seat was unsuccessful, but she returned to politics in 1962 and secured a seat in the Hawaii State Senate. Then in 1964, the U.S. House of Representatives added a second House seat, and – as Shirley Chisholm had also benefited from re-districting – Mink ran for the new Congressional position. Mink won, making history as the first woman of color and the first Asian-American woman to serve in the U.S. Congress, launching her on a lifetime of political service.[21]

As a Congresswoman, Mink was a passionate advocate for gender and racial equality, as well as affordable childcare and bilingual education. She played a key role in authoring and sponsoring Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in educational programs receiving federal funding.[22] Mink was also an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War. Despite working in Washington, D.C., Mink remained committed to her constituents in Hawaii and traveled back to the state every other week to stay connected to their issues and concerns – which in these early days was a full day’s journey. She served on several House Committees, including the Committee on Education and Labor, the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, and the Budget Committee, where she fought for the rights of marginalized groups.[23]

Building her name in anti-war activism, Mink was approached by the Oregon Democratic Party and asked to run for President on an anti-Vietnam War platform. Frustrated with the Nixon administration’s rollbacks of civil liberties, Mink entered the race for the Democratic nomination in 1971, becoming the first Asian-American woman to run for President.[24]

Mink continued to remain active in politics, serving as the President of the Americans for Democratic Action, and later as the Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs. Mink was also reelected to the U.S. Congress in 1990 and served six additional terms. During her tenure, she established the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus and authored significant legislation supporting equality, education, and an end to the Vietnam War[25]. Mink passed away in 2002 due to pneumonia, but her name still appeared on the ballot in the upcoming election, which she won by a large margin. Following her death, Title IX was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act in recognition of her contributions to gender equality[26].

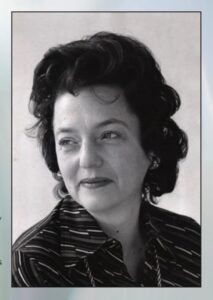

Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin was the first woman to serve in the U.S. Congress, and was the first female to serve in any federal office in the United States.[27] When she cast her vote for women’s suffrage in 1919, she became the first woman to legally vote federally for the right for women to vote. A farm girl from the Montana territory, Rankin knew she was forging a path for others: “I may be the first woman member of Congress,” she said, “but I won’t be the last.”[28]

A pacifist from a Scottish farming family in rural Montana before statehood, Rankin was raised doing all the work on the family’s ranch, including everything from building stalls and furniture construction, to cleaning and maintaining farm machinery, to wrangling large animals – laboring side by side with her brothers and sisters as equals.[29] Her mother was a teacher, and a pacifist with a progressive outlook. After her father’s death in 1904, Rankin became responsible for her younger siblings and embarked on a career, a path that took her to San Francisco, Seattle and eventually, New York and Washington, D.C., in the company of the early Suffragettes.[30]

Rankin eventually became a social worker and spokesperson for universal suffrage, returning to Montana where she became the first woman to speak before the Montana State Legislature, in support of enfranchisement in her home State.[31] After her lobbying, Montana became the seventh state to grant women unrestricted voting rights – but that was just the beginning for Rankin. She coordinated additional state efforts in New York as well as North Dakota and other territories. Her commitment heightened further during the Great War.[32]

Rankin ran for federal office to achieve universal suffrage and with the goal of objecting to World War I. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Montana in 1916, served one term, and then ran again during World War II against that war, and – undeterred – ran and was elected yet again in 1940.[33] As of 2022, Rankin is still the only woman ever elected to Congress from Montana.[34]

Each of Rankin’s several U.S. Congressional terms coincided with the initiation of U.S. military intervention in one of the two World Wars.[35] Rankin was a life-long pacifist and strictly convicted to non-violence; hence one of her motivations in lobbying for legislation enfranchising women to vote in the Western states, and ultimately in the U.S. federally, was to shore up the numbers of people to vote against entering the Great War in 1917.[36] She was one of 50 U.S. House members opposing the First World War in 1917, and later she was the only member of the US House of Representatives voting against the declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor. [37]

In 1918, Rankin introduced the legislation that became the 19th Amendment, granting unrestricted voting rights to women nationwide.[38] She stood in the U.S. House of Representatives and made a historic argument – appealing not just to her commitment to pacifism, but to the equities of women supporting their country, yet not participating fully in civic life and global politics.[39] Rankin was describing what would later become the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. Millions of women across the US had sacrificed and labored in “the Great War,” she argued, yet without civic rights.[40]

Much like “Rosie the Riveter” three decades later, in the Great War women had filled jobs left behind by men who had gone to battle, and taken up new positions and work created by the war effort, she told her fellow legislators.[41] But still, women across America did not have the right to vote. How unfair, Rankin said, to rely on women’s wartime contributions and personal sacrifices in the fight for democracy — and then deny them the full rights of citizenship.[42] Democracy should begin at home, she said. “Today there are men and women in every field of endeavor who are bending all their energies toward a realization of this dream of universal justice. How shall we answer their challenge, gentlemen; how shall we explain to them the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted for war to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?”[43] That resolution narrowly passed in the House, but died in the Senate.

A year later, Rankin, reason and justice prevailed. Congress passed the same resolution by overwhelming margins. In 1920, the 19th Amendment was added to the Constitution, having been introduced by Rankin, who went on to author the Amendment.[44]

Rankin never stopped being committed to non-violence and agitating over the decades, along with her close friend, journalist Katherine Anthony.[45] Rankin mobilized for peace during World War II and subsequently against the Korean War and, well into her 90s, against the Vietnam War. Her life was dedicated to disarmament and advocating for civic engagement and unrestricted roles for women in leadership as the key to international peace and prosperity.[46]

-Heidi Reavis

Dedicated to all the Mothers in my life, and especially to my Mother, Thetis T. Reavis, who was also strongly influenced by World War II, attended Smith College and The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy during the post-War era, and dedicated her career to international cooperation and foreign policy education with Voice of America, the United Nations, and over 30 years with The Foreign Policy Association, a non-profit organization producing educational material for schools, universities and legislators on major foreign policy issues.

Dedicated to all the Mothers in my life, and especially to my Mother, Thetis T. Reavis, who was also strongly influenced by World War II, attended Smith College and The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy during the post-War era, and dedicated her career to international cooperation and foreign policy education with Voice of America, the United Nations, and over 30 years with The Foreign Policy Association, a non-profit organization producing educational material for schools, universities and legislators on major foreign policy issues.

[1]History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Historical Data.” Historical Data | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

[2] Michals, Debra, “Shirley Chisholm.” National Women’s History Museum, 2015. Shirley Chisholm | National Women’s History Museum (womenshistory.org)

[3] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Chisholm, Shirley Anita.” CHISHOLM, Shirley Anita | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

[4] Id.

[5] Id. at 2

[6] Id.

[7] Id. at 3

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Speaking While Female Speech Bank, “It is Time to Reassess Our National Priorities.” War – Chisholm – Speaking While Female Speech Bank

[11] Id.

[12] Alexander, Kerri Lee, “Patsy Mink.” National Women’s History Museum, 2019. Patsy Mink | National Women’s History Museum (womenshistory.org)

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics, “The Jeannette Rankin Foundation,” Iowa State University, 2021. Jeannette Rankin | Archives of Women’s Political Communication (iastate.edu)

[28] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Rankin, Jeannette.” RANKIN, Jeannette | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

[29] Mary Barmeyer O’Brien, “Jeannette Rankin: Bright Star in the Big Sky” 2015 Jeannette Rankin: Bright Star in the Big Sky – Mary Barmeyer O’Brien – Google Books

[30] Id.

[31] National Constitution Center, “On This Day: Jeannette Rankin’s History-Making Moment.” On this day, Jeannette Rankin’s history-making moment | Constitution Center

[32] Id.

[33] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Representative Jeannette Rankin of Montana” Representative Jeannette Rankin of Montana | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

[34] History, “7 Things You May Not Know About Jeannette Rankin” 7 Things You May Not Know About Jeannette Rankin – HISTORY

[35] Id.

[36] Id. at 16

[37] History, “Jeannette Ranking Casts Sole Vote Against WWII” Jeannette Rankin casts sole vote against WWII – HISTORY

[38] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “The House’s 1918 Passage of a Constitutional Amendment Granting Women the Right to Vote” The House’s 1918 Passage of a Constitutional Amendment Granting Women the Right to Vote | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

[39] Id. at 16

[40] Id.

[41] History, “Rosie the Riveter” Rosie the Riveter – Real Person, Facts & Norman Rockwell – HISTORY

[42] Speaking While Female, “On Women’s Rights and Wartime Service, Jeannette Rankin” Womans vote – Rankin – Speaking While Female Speech Bank

[43] Id.

[44] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Whereas: Stories from the People’s House – Jeannette Rankin and the Women’s Suffrage Amendment” Jeannette Rankin and the Women’s Suffrage Amendment | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

[45] Id.

[46] American Heritage, “The Woman Who Said “No” to War” The Woman Who Said “No” to War | AMERICAN HERITAGE

ge, “The Woman Who Said “No” to War” The Woman Who Said “No” to War | AMERICAN HERITAGE