Honoring Herstory: The North American “Forefather” of the Home Security System Was a Mother (of Invention)

As we close Black History Month and Women’s History Month, we take this moment to honor a woman whose innovations are relied upon in many households and businesses today, while hers is still not a household name.

Nearly 60 years ago in 1966, African American nurse Marie Van Brittan Brown lived in Jamaica, Queens, New York. As a nurse, she worked irregular hours and would come home late at night or spend nights on her own because her husband, Albert Brown, an electrician, also spent long and odd hours at work, away from home. Marie Van Brittan Brown was often concerned about her safety when home alone.

Feeling secure is a central component of our well-being. Unfortunately, the reality is that this universal need is still a luxury many cannot afford – particularly for people living in socioeconomically vulnerable areas. Marie Van Brittan Brown determined to devise a system that could help her surveil her home and alert the police if an intruder showed up. Together with her husband Albert, she invented the first closed circuit home security system, for which they were granted a patent by the United States Patent Office in 1969. The patent, U.S. Patent 3,482,037, names Marie Van Brittan Brown as the principal inventor.

The Invention

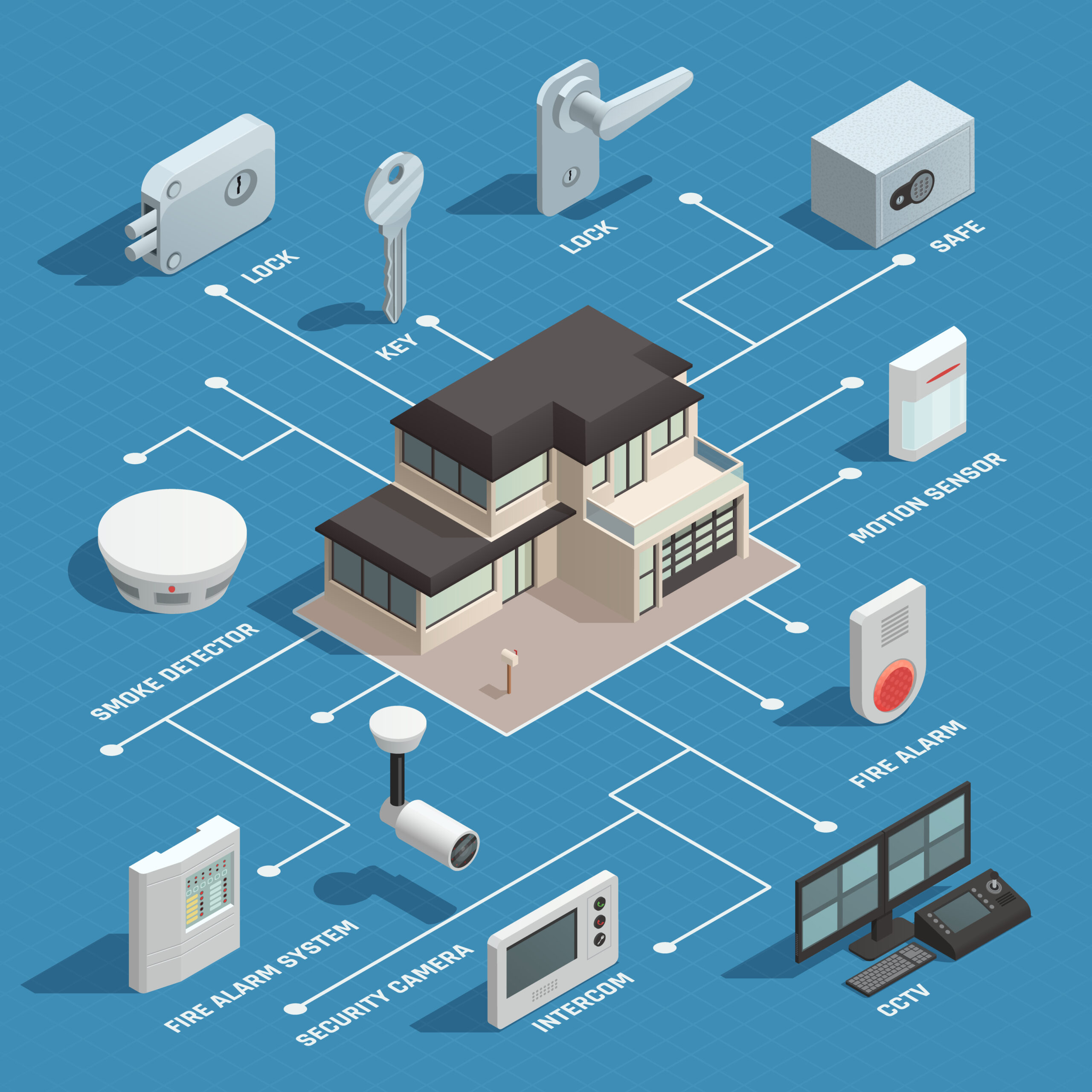

Brown’s s residential security system was comprised of four vertical peepholes on the front door, a sliding camera, television monitors, and microphones. The system allowed the home occupant to see who was at the door and communicate with that person with the help of two-way microphones (“intercommunication” equipment) – and, to remotely open the door by the simple pushing of a button. The system also included a radio-controlled alarm for sending an external alarm to a guard, policeman or watchman at a security station, and a closed-circuit television, which today is known as CCTV.[1]

Not a Household Name

This ingenious home surveillance system is still of utmost relevance today, modified over time to apply to “banks, office buildings, and apartment complexes.”[2] According to the Washington Post, “… video surveillance is a massive and fast-growing industry, with a global market that was worth $45.5 billion in 2020 and is expected to exceed $60 billion in 2023.”[3]

Despite this fact and the near ubiquitous presence of home and commercial video security systems, have you ever heard of Marie Van Brittan Brown?

In researching for this article, we were surprised to learn that, after the immediate attention she received following her patent receipt – The New York Times published the news of her invention on December 6, 1969, just four days after Brown received her patent – Brown fell into relative obscurity. Despite the fact that she failed to become a household name, Brown is considered the “mother” of the field, and her patent has been cited in 38 patent applications[4]. Although Brown was crucial to the modern-day home and commercial security system industry, she, along with many other Black inventors, remains relatively unknown outside of a handful of online articles.

This lack of notoriety is consistent with the history of exclusion regarding innovations accomplished by women and people of color. African Americans who were indentured were not allowed to hold patents at the outset of the U.S. Patent system. This was for two “reasons”: (i) they were considered property, and their inventions were considered to belong to their White owners; and (ii) they were not considered citizens of the United States.[5]

Another Black inventor and trailblazer was Thomas L. Jennings, the first African American ever to hold a patent. Jennings’ patent was for dry scouring, the precursor to dry cleaning. The profits from his business were utilized by Jennings to purchase the freedom of his wife and children.[6]

Benjamin Banneker, a self-taught mathematician and inventor of the striking wall clock as well as the almanac, gifted the first edition of his almanac to Thomas Jefferson, and later used this connection to Jefferson to encourage Jefferson to acknowledge, in political conversations regarding race, that Black people had talents equal to those of other races and should be fully recognized.[7]

Sarah Breedlove Walker is known for inventing the first hot comb and pomade – hair styling tools still used today – significant in reducing the harm associated with straightening hair via scalding clothing irons and other products not designed for this purpose.[8]

And still, these Black inventors are just barely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to innovators of color, non-White inventors, and women inventors in the United States.

Many of the inventors discussed above not only overcame incredible systemic injustices, cost and risk in creating their inventions, but actively acknowledged and fought against those injustices. Whether using the profits from a patent to buy a loved one’s freedom, utilizing contacts to encourage political action, establishing a product that reduces harm, or, as with Brown, creating a product to increase security, they worked hard and inventively, against the tide, to have an impact for themselves and their country – yet were rewarded in history by being forgotten.

We note that many reports that we reviewed for this article regarding Black inventors were written in February, Black History Month in the United States. The same is true for women inventors during Women’s History Month. This demonstrates the benefit of holding and elevating Black history and women’s history into the light; however, it also highlights the general inadequacy of recognition of the accomplishments of all people who are striving to innovate.

Just as we strive to diversify our educational institutions and workplaces, it is vital to diversify the “inventive space” and strive to make STEM studies more appealing to women and historically underrepresented and marginalized groups. Making such progress into the future involves acknowledging the work of inventors in the past; understanding their stories; acknowledging their challenges; respecting them; spreading the word about those inventors whose lives and innovations are part of our shared history.

[1] See U.S. Patent 3,482,037.

[2] See https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/marie-van-brittan-brown

[3] See https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/02/01/marie-brown-video-home-security/

[4] See https://patents.google.com/patent/US3482037A/en

[5] See https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/300-years-of-african-american-invention-and-innovation/; see also Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 US 393 (1857).

[6] See https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/jennings-thomas-l-1791-1856/

[7] See https://www.whitehousehistory.org/benjamin-banneker

[8] See https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/madam-cj-walker

This article is intended as a general discussion of these issues only and is not to be considered legal advice or relied upon. For more information, please contact RPJ Associate Nafsika Karavida who counsels clients on employment, intellectual property, corporate and transactional, and cross-border commercial law. Ms. Karavida is admitted to practice law in Connecticut, New York, Sweden, the European Union, and before the United States Patent and Trademark Office (limited recognition, passed Patent Bar Exam March 2023, admission pending).