Netflix’s “Our Father”: A Fertile Ground for Lawsuits and Legal Drama

by Daniel Ain and Ariana Zhao

Netflix is no stranger to litigation brought by individuals unhappy with their appearance or portrayal in Netflix programming.

My colleagues have previously commented on recent defamation claims in scripted Netflix series, including Baby Reindeer and Inventing Anna.

A case decided last week in the Southern District of Indiana, Bowling v. Netflix, Inc., Case No. 22 CIV. 01281 (TWP) (MJD), is particularly noteworthy for two reasons: (1) the allegations were, in part, based on invasion of privacy (rather than defamation), specifically public disclosure of private facts; and (2) some of plaintiffs’ claims withstood two motions for summary judgment and proceeded through jury verdict.

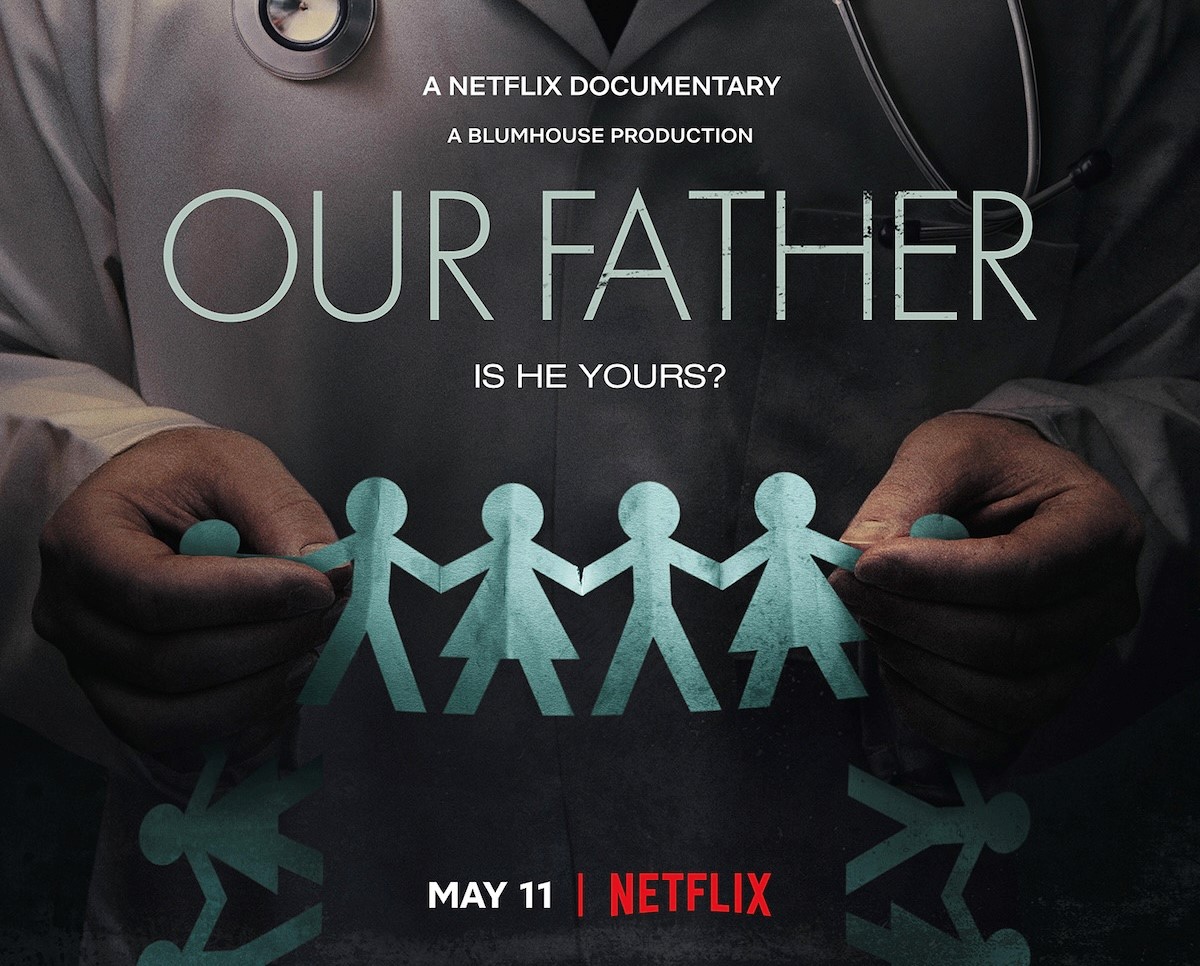

The film at issue was the documentary Our Father, produced by RealHouse Productions LLC (the documentary division of Blumhouse Productions) and distributed by Netflix. Our Father centers around former Indiana fertility doctor Donald Cline’s shocking behavior: inseminating his fertility patients with his own sperm without their knowledge or consent, resulting in the births of over 90 children who share him as their biological father. His actions came to light with the proliferation of the at-home DNA testing service 23andMe. At the time of Dr. Cline’s actions, Indiana had no “Fertility Fraud” crime on the books, however, he eventually pled guilty to other criminal charges.

When RealHouse and Netflix made Our Father, it obtained releases from those participants who consented to appear in or be identified in film. However, it mistakenly revealed the identities of some of the half-siblings who had not provided consent in fleeting moments in both the film and in the film’s trailer. Three of these individuals, Sarah Bowling, Lori Kennard and Laura DiSalvo, sued RealHouse and Netflix.

In order to succeed on a public disclosure of private facts claim, a plaintiff needs to prove the following:

- the defendant “gave publicity” to the facts in question;

- the facts were private (i.e., not generally known);

- publication of the private facts was offensive to a reasonable person; and

- the facts disclosed were not newsworthy.

The public disclosure of private facts claim by one of the three plaintiffs, Ms. DiSalvo, was dismissed at an earlier stage because her identity was deemed not to be “private.” Ms. DiSalvo had taken steps to publicize her story and identity, including to a local reporter and on her Instagram account.

Certain other of the plaintiffs’ claims failed to survive defendants’ motions for summary judgment, including claims of identity deception, identity theft, and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

The public disclosure of private facts claims for the two remaining plaintiffs, Ms. Bowling and Ms. Kennard, were permitted to proceed. In its order on defendants’ first motion for summary judgment, the Court reasoned that plaintiffs had sufficiently alleged that defendants’ disclosure of their identities was dissimilar in nature to their own voluntary disclosure to a select group of persons (namely, their possible half-siblings), and that their identities were purely private matters as opposed to being newsworthy. However, the Court later determined that any award would be limited to compensatory damages. Punitive damages were off the table.

After seven hours of deliberations, a jury returned a verdict holding RealHouse and Netflix responsible in the amount of $385,000 in connection with Ms. Kennard’s claim and not responsible in connection with Ms. Bowling’s claim. Evidence that Ms. Bowling had revealed her identity to others and that her mother had posted on Facebook about her status as a child of Dr. Cline may have been the reason for the split verdict.

The case is significant because of how rare tort cases against distributors, such as this one, proceed to verdict, and the fact that the jury ultimately held the defendants responsible. While precedent setting, it is worth noting the relatively modest damages awarded by the jury. $385,000 is not likely to sting a streaming giant with an annual $17 billion content budget any more than a slap on the wrist would.

This article is intended as a general discussion of these issues only and is not to be considered legal advice or relied upon. For more information, please contact RPJ Counsel Daniel Jason Ain who counsels clients in areas of entertainment, media and literary, intellectual property and employment law. Mr. Ain is admitted to practice law in the State of New York and the District of Columbia.